Arctic Urbanism in Canada's North

A different understanding of urban development, where climate change and respect for the land influence northern living.

At this time of year during the summer months, I've always wanted to visit Canada's northern territories — the land of the midnight sun — to witness the sun looping in the sky without setting for days, and explore its rugged landscapes, world-class geology, and magnificent wildlife, such as beluga whales and caribou.

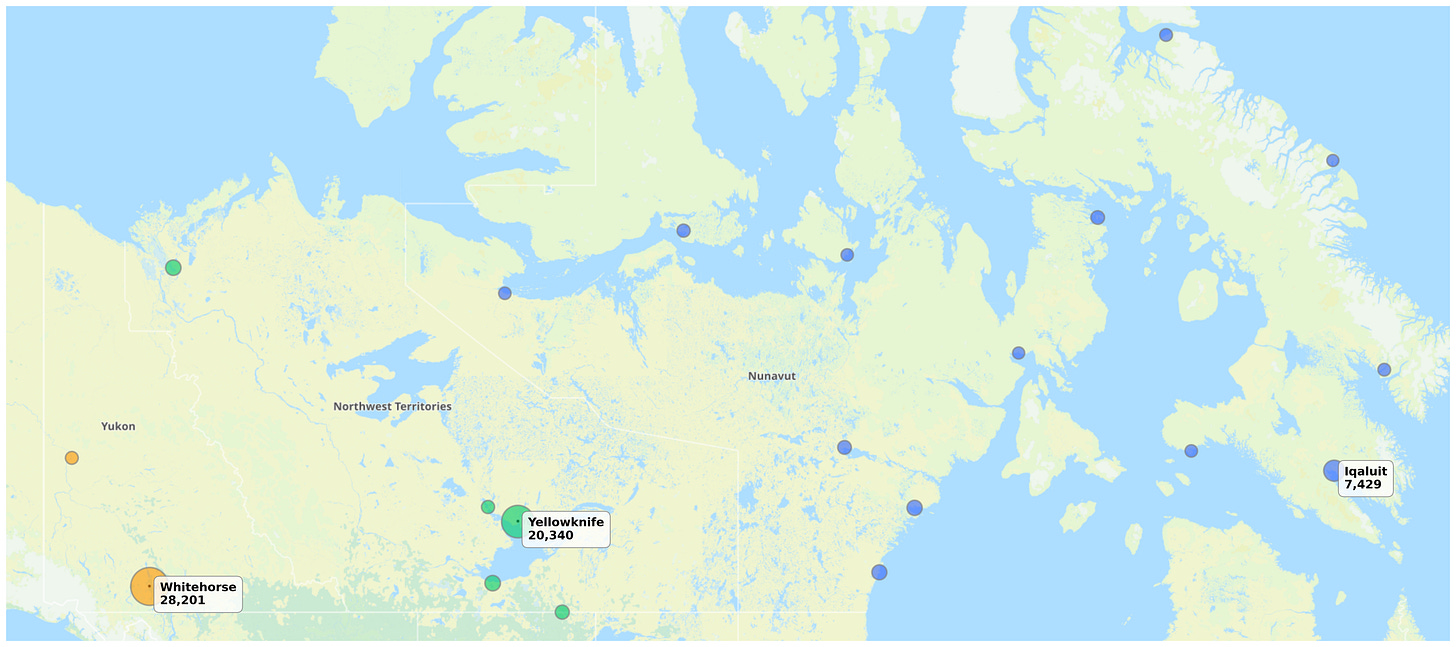

Canada’s north encompasses a vast 40% of the country’s landmass, yet it’s home to only approximately 114,000 people across the Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Nunavut. This translates to a remarkably low population density of roughly one person per 30 square kilometers, a testament to the region's extreme climate and limited daylight outside of summertime.

Built Environments in the Cold

Indigenous and Inuit populations have flourished in the region for millennia, adapting to its frigid, harsh conditions. However, the 20th century brought a wave of global industrialization and modern urban planning that sought to reshape these long-established communities, viewing the North as a testing ground for ambitious experiments. Often naively and negligently conducted, these experiments disregarded traditional knowledge and practices in an effort to conquer the harsh winter climate.

This approach coincided with a broader colonial government policy of assimilation, aimed at integrating Indigenous and Inuit populations into a modern, Western way of life. As a prominent example, the Canadian government commissioned British architect Ralph Erskine to design a model Arctic town at Resolute Bay, featuring novel cold-climate urban design.

The Concept of “Nordicity”

In the 1960s and 70s, Québec geographer Louis-Edmond Hamelin introduced the concept of "nordicity", which highlights the distinct polar values and conditions of northern communities. The extremes of the midnight sun and long, cold winter nights foster a unique appreciation for the functional value of place, shaped by shared community and cultural experiences across vast distances and changing seasons. The conventional ideas of 'city’ and ‘urban environment’ aren’t quite as relevant here.

Nunavut, established in 1999 as Canada’s largest territory, adopted a decentralized governance model due to its vast landmass, challenging Arctic and Sub-arctic conditions, and the desire for a less hierarchical, more accessible government for its dispersed populations.

However, this structure has presented practical and environmental challenges. Fossil fuels remain heavily relied upon for everyday power needs, making energy expensive; sustainable alternatives, like solar and wind power, remain difficult to implement due to reduced sunlight and extreme cold that strains infrastructure. Aviation is crucial for long-distance transportation, while informal snowmobile and ATV paths, independent of the formal road network limited by pervasive ground permafrost, create a vital seasonal transportation network essential for maintaining social connections and cultural traditions.

Defining Canada’s North

The Arctic regions are among the most vulnerable to rising global temperatures. The thawing of permafrost is reshaping the landscape and deteriorating existing infrastructure, such as roads, airstrips, and buildings, disrupting mobility between northern communities. While melting sea ice opens up new waterways for shipping and uncovers resources like oil, diamonds, and rare earth minerals, promising significant economic growth, these changes also raise critical questions about national security and environmental protection.

Canada has an opportunity to navigate these complex challenges by supporting a vision for northern urbanization that respects and incorporates the diverse cultures and traditions of its communities, acknowledging that Indigenous peoples make up a significant proportion of the population in each territory: 86 percent in Nunavut, 51 percent in the Northwest Territories, and 23 percent in the Yukon. A recent investment of over $1.4 million in projects across Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, and Yukon from the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor) is an encouraging step, aimed at upgrading infrastructure, adopting digital platforms, and training and preparing the workforce for a sustainable and prosperous future.

It’ll be interesting to see how a distinct Canadian Arctic urbanism takes shape, balancing economic development with environmental protection and cultural preservation.