Biophilic Cities: A Natural Urban Future

From Toronto: exploring how cities are reimagining urban spaces by integrating nature to create more livable, sustainable, and resilient environments.

Can a city densify without losing its connection to nature?

That’s an intriguing question posed on a construction board for King Toronto, an ambitious new urban development project in Toronto’s King West neighbourhood.

It plans to build with a mix of heritage and modern building materials, characterized by hundreds of modular terraces weaved with natural elements and accessible communal spaces. Complementing the existing parks, amenities, and transit options in the surrounding area, especially with the upcoming King-Bathurst subway station, it’s a bold attempt to evolve urban living, harmonizing density with the natural environment in the heart of the city.

Biophilia: A Love of Life

Biophilic urban planning is a global movement that’s reshaping our cities. By incorporating natural elements into built environments, biophilic design aims to improve citizens’ well-being, generate economic benefits, and add resilience against the increasing threat of extreme weather events.

The term 'Biophilia', coined by psychoanalyst Erich Fromm in the 1960’s, stems from the Greek meaning of “love of life or living things”, and later popularized by biologist Edward O. Wilson in 1984 with theories from his book of the same title. It's rooted in the belief that humans have an innate need to connect with the natural world.

The concept gained traction through the work of visionaries like Stephen R. Kellert, a Yale professor who scientifically demonstrated nature's positive impact on human health. And starting from the 1960s, Danish architect Jan Gehl advocated for human-centred urban design, prioritizing pedestrians and public spaces over cars. Their work, along with contributions from others, laid the foundation for today's biophilic design principles.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted our need for nature in urban spaces, as many of us found comfort and connected with the outdoors during lockdowns, whether through gardening, adding plants to our homes, or simply spending more time outside. This collective experience has reinforced the value of integrating green spaces into our cities for their crucial role in promoting physical and mental health, mitigating climate change impacts, and fostering social connection.

Revising the Concrete Jungle

The concept of biophilia seems straightforward now, but 20th-century urban development patterns, especially in North America, often undermined this principle. The post-World War II era saw a surge in consumerism, fueled by rapid industrialization and emerging technologies that promised an enviable lifestyle. This, coupled with urban sprawl due to the rise of the automobile, culminated in the creation of car-centric, industrialized cities marked by concrete, steel, and lots of oil, reflecting a desire to dominate nature rather than coexist with it.

Dense networks of highways were designed to facilitate long-distance travel by car, which has disrupted social cohesion within city neighbourhoods. Early brutalist architecture, with its emphasis on exposed concrete, and modular, geometric elements, reflected a sense of urban detachment from the natural world and mirrored the anxieties of modern life. For some time, cities prioritized machines and efficient infrastructure driven by endless growth over human-scale interactions and long-term sustainability.

The Biophilic Street: Reimagining Urban Spaces

While parks have traditionally been the focal point of urban greening, attention is now shifting to where people spend most of their time: the streets. This shift in focus aims to integrate nature into the everyday fabric of city life, recognizing that streets are not just for mobility but vital public spaces.

A recent framework from Sustainable Earth Reviews, a community-focused journal, proposes six categories for the ‘Biophilic Street’:

Traffic planning: Trees and bushes can psychologically encourage drivers to slow down, reducing accidents and improving safety.

Energy management: Trees and vegetation can reduce building emissions by providing shade and insulation, thus lowering energy consumption for cooling.

Stormwater management: Green infrastructure like rain gardens and permeable pavements can help manage stormwater runoff and mitigate flooding by absorbing and filtering rainwater.

Biodiversity management: Urban green spaces can support a variety of plant and animal species, contributing to a healthier ecosystem and enhancing biodiversity.

Street furniture: Benches, planters, and other elements can be designed to incorporate natural materials and patterns, enhancing the aesthetic appeal of streets and creating a more inviting environment.

Education: Informative signage and educational programs can help raise awareness about the benefits of biophilic planning and encourage people to engage with nature in their urban environments, fostering a sense of stewardship and connection.

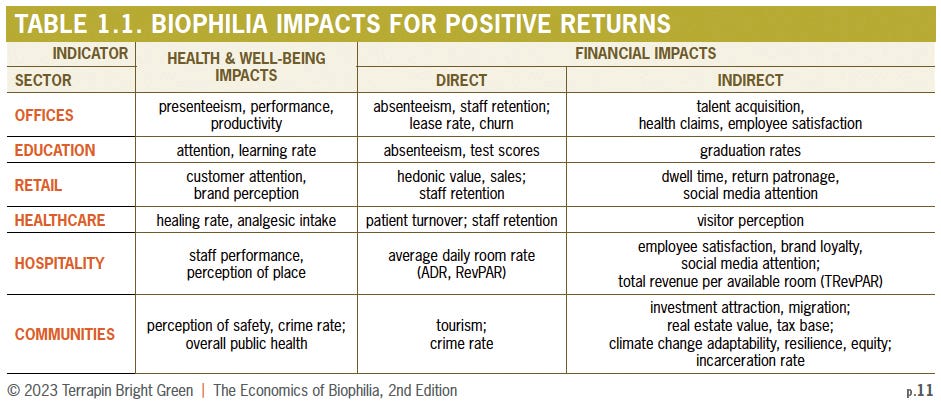

Investing in Nature for Economic Returns

Beyond its aesthetic appeal and established benefits for human productivity, preferences, and health, many studies highlight the tangible financial returns of exposure to nature, underscoring the need for further investment in biophilic design.

Examples include:

Healthcare savings through reduced chronic diseases in green communities

Crime reduction correlated with increased tree canopy density

Property value increases from street trees, boosting tax revenue

Reduced energy costs from green roofs and walls that lower heating and cooling expenses for buildings

Increased worker productivity from offices with natural elements

Additionally, a recent report from the Canadian Urban Institute (CUI) and Natural Assets Initiative (NAI) recognizes the untapped economic potential of natural assets in Canada, such as wetlands, forests, parks, lakes, rivers, and fields, which can play crucial roles in federal priorities for infrastructure resilience, net-zero targets, and 2030 biodiversity targets. Given a rapidly growing population, critical housing shortages, and a changing climate, it strongly advocates for evolving federal housing policies with sustainability at its core.

These initiatives draw inspiration from places like Paris and Singapore, along with the traditional ecological knowledge of Indigenous communities, who have a deep understanding of sustainable land management practices and have been stewards of the land, water, soil, and air for millennia.

Greener, Smarter Cities

In the face of the escalating climate crisis, and as we approach two degrees of global warming, biophilic design and natural asset management must be essential components of urban planning.

For thousands of years, humans lived outside among fields and trees, with our senses attuned to sunlight, open air, and the sounds of running water. However, centuries of civilization and city building have distanced us from these natural rhythms. Thoughtfully merging our built and natural environments, in ways that resonate with our biology, can improve overall physical and mental well-being while also benefitting businesses.

Recognizing that cities are on the front line of climate action, there has been growing enthusiasm for technology to optimize resource use and enable utopian visions of smart cities. This involves AI-powered sensors and other smart technologies to optimize building energy usage, traffic flow, waste management, and more. However, they’ve also faced challenges like data privacy concerns and criticisms that these new developments can feel cold and homogenous, lacking in character and soul.

Biophilic urban design offers a way to humanize these essential technological advancements into our existing spaces, creating a realistic vision of thriving urban centres that integrate nature and technology in a more balanced way.